Digital technology has changed our governments over the past three decades. Sometimes for the better—sometimes less so.

On the bright side, many of us can now renew our passports and driving licences online, receive real-time alerts for floods and similar emergency events, and access our medical records.

Digital teams have done some great work often in difficult circumstances. Yet none of these changes happened overnight.

Many took years of hard work, the backing and repeated interventions of committed politicians, and dogged persistence.

Background

When the UK’s tax agency first let citizens file their tax over the internet in 2001, there were just 38,000 returns.

In 2023, there were 11.5 million. However, this impressive growth also illustrates the lack of a more radical digital transformation: the “increasingly complex tax system burdens government and business with billions in admin costs.” Every year, millions of people are forced to go online to fill in electronic versions of paper forms. A truly transformed public sector would eliminate form-filling, not suck ever more people into the system.

Sometimes government use of technology also heralds something darker: digital welfare systems that breach the rule of law; public agencies trawling citizens’ bank accounts without their consent; CCTV cameras recording our every movement; citizens demoted to second class status as “digital by default” interactions take priority over all other channels; national identity systems that intrude into citizens’ lives and disadvantage the most vulnerable; authoritarian regimes tracking and repressing political dissidents.

The vision versus the reality

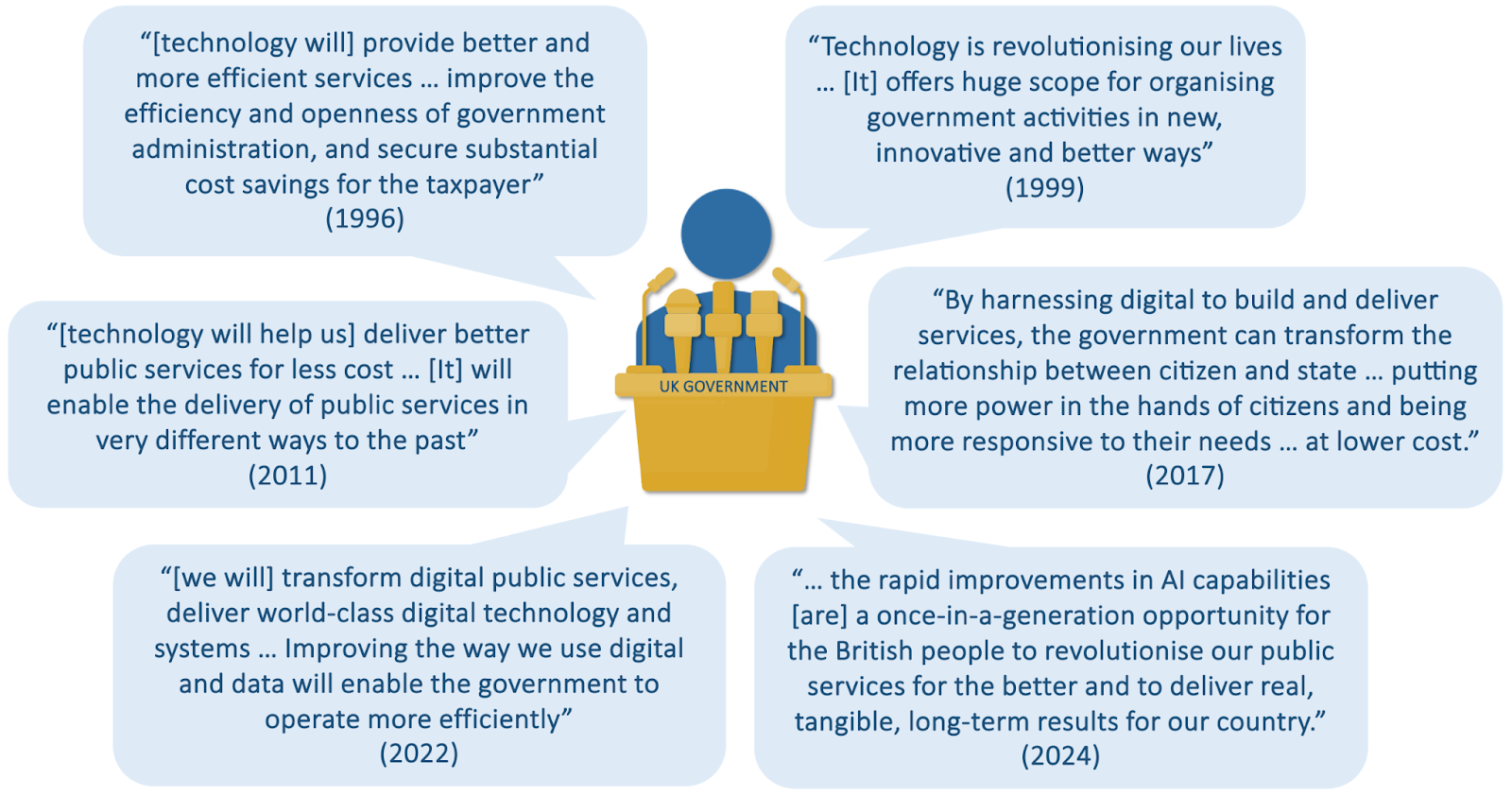

Excited by visions of a more open and participative democracy, by the late 1990s the UK government saw how technology could:

“Facilitate fundamental changes in the relationships between the citizen and the state, and between nation states, with implications for the democratic process and structures of government.”

By 2002, the UK government was busy consulting on ways:

“To promote, strengthen and enhance our democratic structures … [and] to give individuals more choice about how they can participate in the political process.”

The ambition was not only to reverse the decline in citizen engagement, but also to fix the dysfunctional (and sometimes tragic) outcomes created by siloed, department-centred policymaking. Government aspired to deliver a more modern model of democracy, with cross-cutting policies, routine citizen engagement, streamlined processes, and better political transparency and accountability.

They were exciting times, times when anything seemed possible, long foreshadowing the ideas of Tim O’Reilly, the publisher and technology pundit. In 2010, he described how technology could create a more effective form of government, delivering Thomas Jefferson’s model of a democracy where everyone can participate in government “not merely at an election one day in the year, but every day.”

However, governments have now spent three decades repeatedly claiming technology is about to magically transform the public sector. So, why hasn’t it happened?

The ever-imminent, tech-driven transformation of the public sector

The Challenge

The longstanding failure to reform has left governments struggling to plan and respond effectively to the growing catalogue of social, economic, and geopolitical problems they face:

“Many of the biggest challenges facing Government don’t fit easily into traditional [government] structures. Tackling drug addiction, modernising the criminal justice system, encouraging sustainable development, or turning around run-down areas all require a wide range of departments and agencies to work together. And we need better co-ordination and more teamwork right across government.”

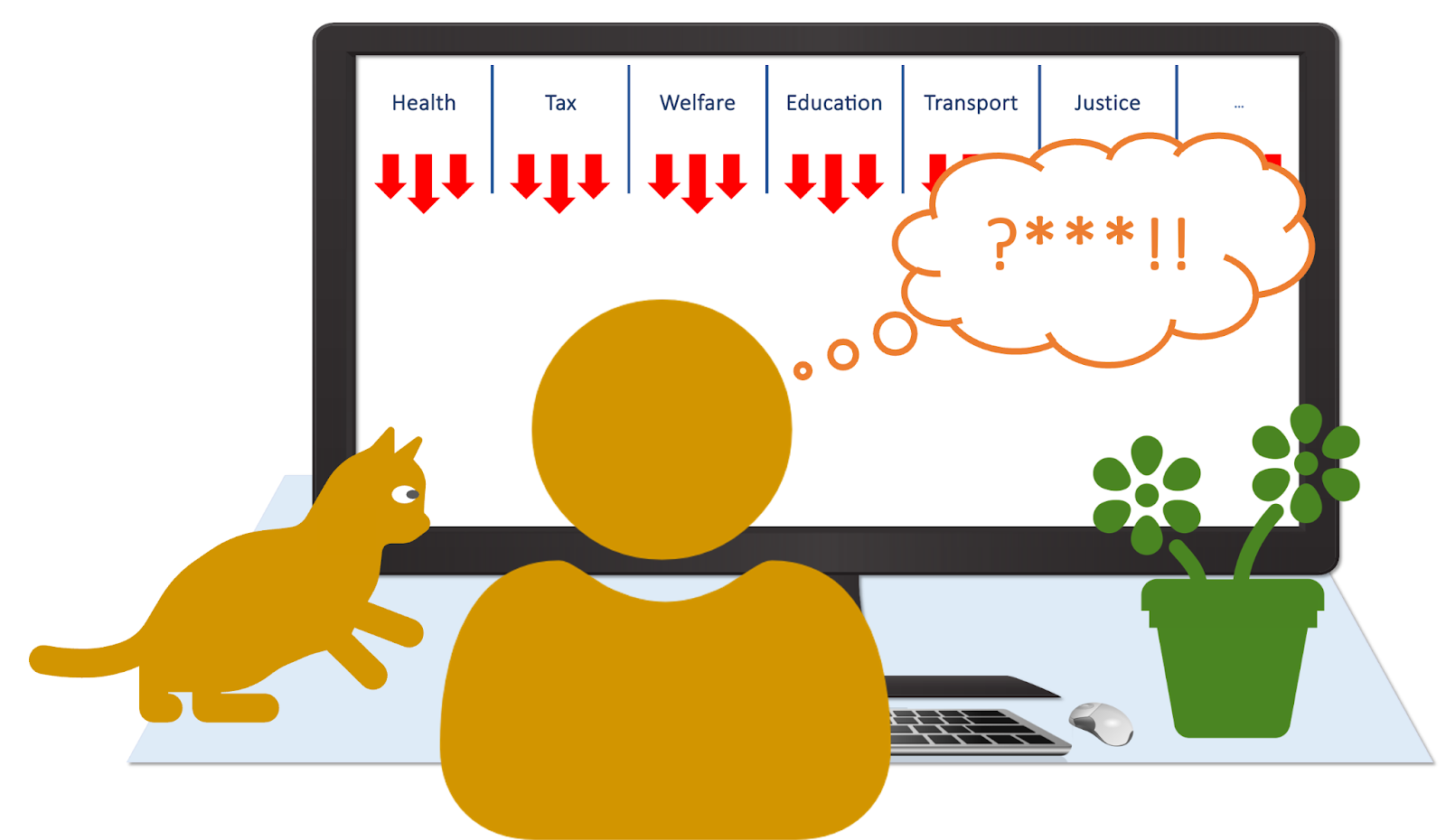

Outside small pockets of success, there’s been remarkably little transformation of government over recent decades. Instead, technology is sidelined into creating digital replicas of existing transactions and processes—sleek websites, online forms, award-winning apps. It automates and fossilises the way things have always been done.

This superficial digital veneer, as the UK government recently called it, masks more fundamental problems: our public institutions are weighed down by antiquated policymaking, paper-era processes, dysfunctional organisational structures, and inadequate constitutional checks and balances on how technology is designed and applied.

The opportunities and challenges of public sector transformation are the topic of many of the articles and blog posts I’ve written during my career—and ultimately the genesis of Fracture. The book grew out of my concern that governments’ failure to modernise leaves them lacking the insights and agility they need to respond with speed, accuracy, and precision.

As a result, they’re haemorrhaging public trust and ill-equipped to handle complex policy challenges such as intergenerational poverty and youth re-offending; the interaction of issues like housing, education, employment, and healthcare; or the growth in domestic and international subversion and threats. These challenges require a:

“Longer-term vision with crosscutting solutions … instead, governing institutions are proving sluggish—adapting and reaching for symbols instead of solutions.”

[The next government of the United States. Why our institutions fail us and how to fix them. Donald F Kettl. 2009]

The last thirty years have seen digital teams like the recently abolished 18F in the US and the Government Digital Service and its predecessors in the UK focus on improving government websites and citizens’ transactional interactions. The experience of online government is now frequently far better than its lacklustre commercial equivalents.

Yet governments don’t exist to create thousands of forms and website interactions, even if it often feels like that. They’re a hangover from how governments worked in the past. They’re not the long-promised “digital transformation”.

Transformation requires the overhaul of governments’ policymaking processes and administration. It means making governments more democratic, transparent, accountable, effective, and efficient: rethinking how they work and eliminating thousands of forms and online interactions in the process.

But the political obstacles to public sector reform are formidable. Machinery of government changes rarely feature in election manifestos. And let’s be honest, we, as voters, are partly to blame. After all, the “machinery of government” isn’t exactly the most exciting and hotly debated political topic during elections. It all sounds so boring and irrelevant on the doorstep.

And yet it’s this rusting machinery that prevents governments from delivering the things we do care about, from housing to healthcare. No wonder it’s “almost impossible to sell voters on drastic reforms until their nation is in acute trouble.”

But waiting for unforeseen crises and acute trouble to force change is dangerous. Our democratic governments and democracy itself are increasingly fragile. They might not survive the next storm. Equally, lazily blaming and demonising civil servants (the “blob”) or pointing fingers at different political parties or politicians or suppliers misses the point. The problem is structural. Our governments were invented for a slower, simpler world.

The Work

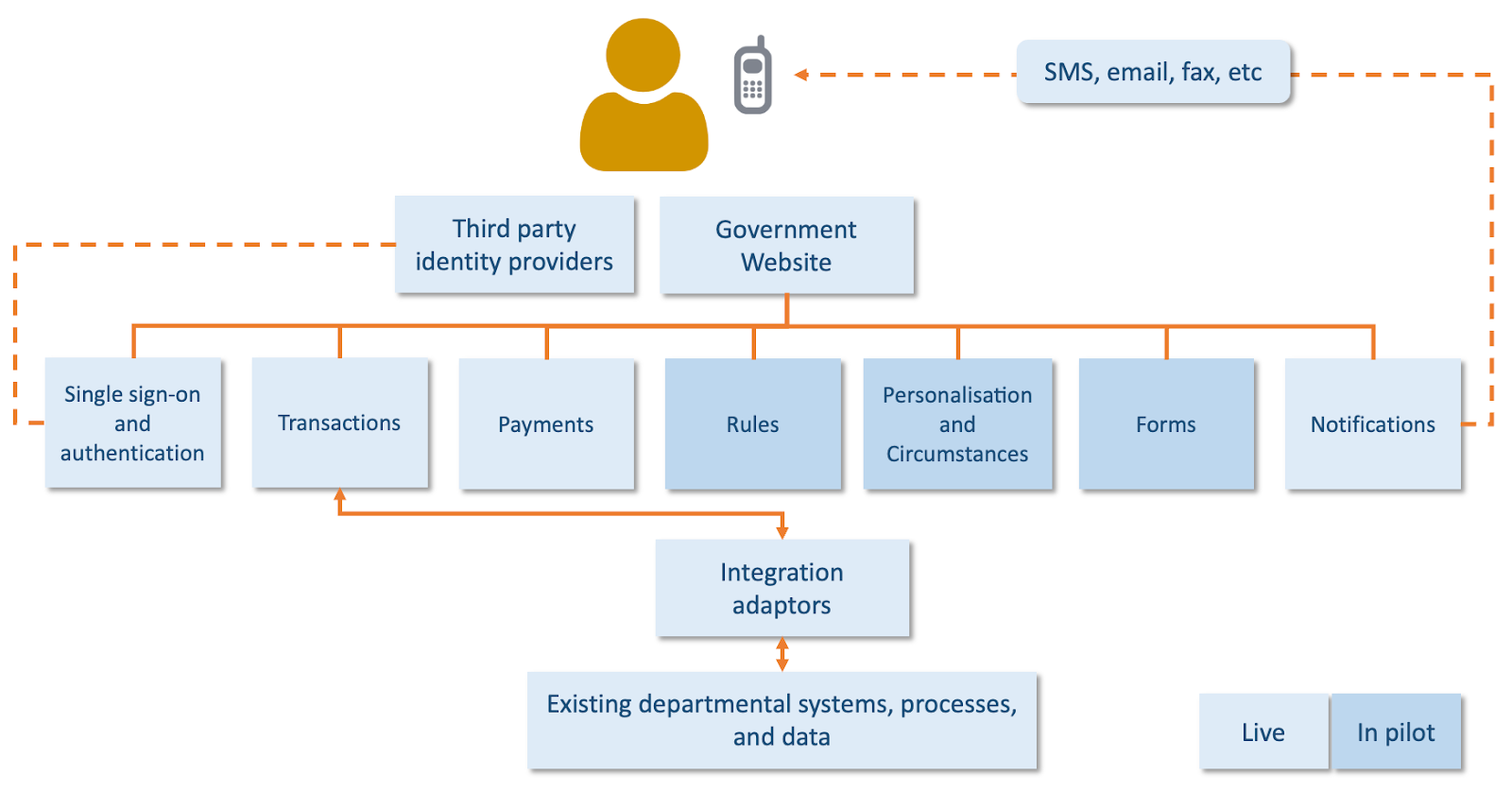

Since the early 2000s, UK governments have repeatedly implemented platforms and shared infrastructure to work across departmental boundaries, meeting common needs such as user authentication, payments, and notifications.

This shared infrastructure helps rationalise and de-duplicate data and processes. It supports the design and implementation of cross-cutting, citizen-centred policies, and streamlined public administration—directly addressing the problem that “many of the biggest challenges facing Government don’t fit easily into traditional structures.”

The role of UK government platforms in 2002

The UK was in the vanguard of implementing common architectures by 2002, and ahead of most other governments in providing secure citizen transactions. But the absence of a sustained political drive to rationalise and improve government meant departments continued to prioritise their own separate transactions and information. Online transactions, and the processes and data behind them, remained as siloed as during the paper era that preceded them—much as they still do today.

Governments have become a poster child for Conway’s law. They use technology to mirror their existing department-centric design instead of improving their organisational structures and operating models to redesign and modernise the state—and democracy itself.

Although some government digital strategies recognise these ambitions—with a focus on cross-cutting policies that better meet citizens’ needs, and a desire to reduce duplication, improve interoperability, and streamline government’s operations—there’s been little sustained momentum with their delivery. Wholesale public sector reform and its associated democratic renewal have made negligible headway over the past thirty years because:

“Departments have failed to understand the difference between improving what currently exists and real digital transformation, meaning that they have missed opportunities to move to modern, efficient ways of working.”

Ask most politicians to define “digital government” today and they’re unlikely to refer to Thomas Jefferson, citizen participation, integrated policy and digital design, and the renewal of democracy. They’re more likely to point at the thousands of paper-era departmental transactions delivered on a central pan-government website and say, “That’s digital!”

Broken digital initiatives deliver endless siloed transactions onto a screen

Governments have acquired an unfortunate habit of digitising existing ways of working—their organisational structures, policies, processes, and transactions—instead of rethinking and redesigning them from first principles. This eternal tinkering with the presentation tier of government flies in the face of the reality that “applying technology to existing working practices, or at the customer interface, will not achieve the full benefits”, as the UK government pointed out in 1996.

As a result, the public sector remains largely unchanged, digitally fossilised into the hierarchies, roles, and operating models of an earlier century. This design may have served governments well in its time, but it’s ill-suited to the complex issues they now face.

The contrast with today’s most effective organisations could not be greater. They use digital technologies and practices to reimagine their structures and operating models, continuously improving how they achieve their objectives. They design themselves for change, transforming their ability to learn, act, and adapt.

Our governments urgently need to do the same:

“Creating, inventing, designing, introducing new processes, new ways of thinking, new forms of leadership and management which enable new ideas to be embraced, new technologies to be exploited and integrated, transforming our current system into one which is permanently innovative, adaptable, responsive, and proactive.”

Digital technologies and practices can help governments plan, deliver, administer, and improve policy outcomes without the deadweight of their legacy organisational silos. They can provide politicians with improved access to data, information, and insights; increase communication and collaboration, allowing citizens, businesses, politicians, and officials to work together on the development of better policy; and enhance democratic transparency and accountability.

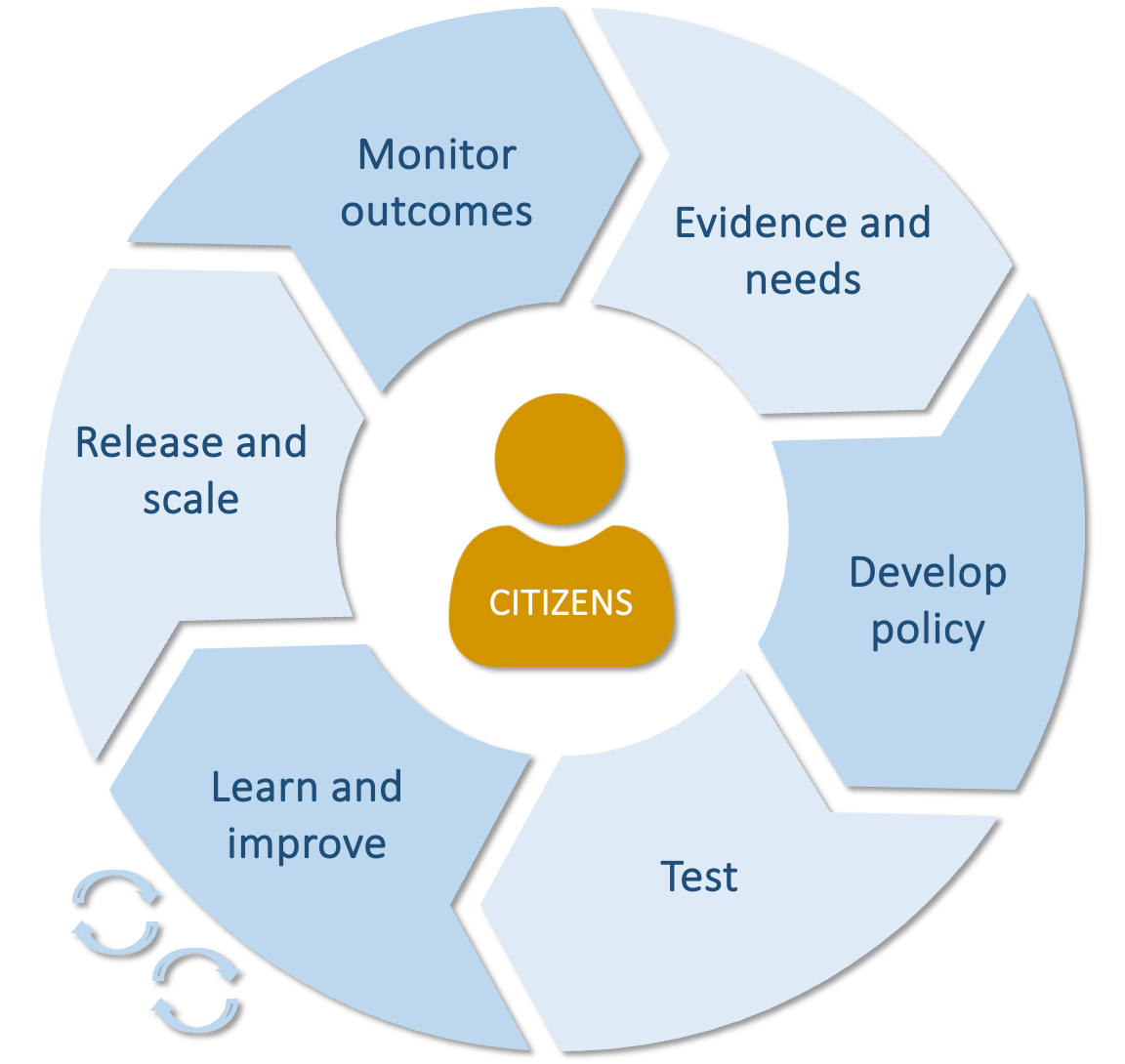

It’s no coincidence that the most successful operating models—from military planning to software development—share similar characteristics. They exploit a perpetual cycle of evidence and needs, development, testing, learning, and ongoing improvement.

Unfortunately, little of this mindset applies to policymaking. Former Permanent Secretary Jonathan Slater points out that:

“Policymaking has always been distant from its customers … Whitehall’s remoteness from the public and frontline results in policymaking which is fundamentally inadequate to address the challenges we face.”

This remote and inadequate approach traps the public sector in a damaging spiral of decline and impedes public sector reform.

The Opportunity

Instead of endless tinkering with the presentation tier—the “digital veneer”—governments should be using digital technologies and practices to develop a more modern and effective approach to policy research, development, testing, and continuous improvement.

The fusion of policymaking and digital practice

They also need to overcome their deeply ingrained bias towards top-down, hierarchical policies, structures, and processes. Networked, collaborative organisations frequently produce better outcomes than top-down command and control. Overly centralised digitised administration erodes democracy, hollowing out essential state capacity and accountability at a local level.

Networked operating models can help to foster an improved form of democratic governance. One that reconciles ideological disputes about central versus local responsibilities. A form of governance where participation, power, resources, and decisions operate at the most appropriate, and accountable level—national, regional, local, or hyper-local. It’s exactly the sort of radical transformation that politicians once aspired to deliver.

How different might our world have been by now if the original bold ambitions for a radical transformation of government had succeeded? How much better and healthier would government be if digital technologies and practices had improved participation, produced fundamental improvements in democracy and our public institutions, and reforged relationships between the citizen and the state? Would we still have seen the growing crisis of confidence in democracy, the loss of trust in politicians, and the rise of divisive populism and nationalism over recent years?

I suspect many of the voters increasingly attracted by the siren call of populist politicians do so in reaction to the repeated failures of our governments: they’re making a cry for help as much as venting their frustration. This growing disaffection is another compelling reason politicians urgently need to make a serious and enduring commitment to the digital transformation of government.

The growing fracture between the evergreen promise of public sector reform and the reality matters. It’s ultimately about the legitimacy and relevance of democracy itself. Modernising government is integral to fixing the problems politicians and voters care about: better healthcare, affordable housing, economic growth, social mobility, education and training, environmental protection—and dozens of equally pressing policy issues.

Our governments can’t continue to fail. The stakes are far too large. They urgently need to jumpstart the public sector’s modernisation; make better use of technology to promote, strengthen, and enhance our democratic structures and institutions; and increase citizens’ participation—and trust—in the political process.

I hope Fracture can play a role in inspiring citizens, politicians, officials, and governments to seize the opportunity to deliver the long-promised digital transformation our democracies so urgently need.

The book

The book

The second edition of Fracture. The collision between technology and democracy—and how we fix it draws on over thirty years of digital transformation initiatives to explore how governments can get their mojo back—and learn smarter, react faster, and adapt better.

Fracture is available as: